BLESSED ARE THE PEACEMAKERS

1. EACH NEW YEAR brings the expectation of a better world. In

light of this, I ask God, the Father of humanity, to grant us concord and peace,

so that the aspirations of all for a happy and prosperous life may be achieved.

Fifty years after the beginning of the Second

Vatican Council, which helped to strengthen the Church’s mission in the

world, it is heartening to realize that Christians, as the People of God in

fellowship with him and sojourning among mankind, are committed within history

to sharing humanity’s joys and hopes, grief and anguish, [1] as they proclaim the salvation of Christ and promote peace

for all.

In effect, our times, marked by globalization with its positive

and negative aspects, as well as the continuation of violent conflicts and

threats of war, demand a new, shared commitment in pursuit of the common good

and the development of all men, and of the whole man.

It is alarming to see hotbeds of tension and conflict caused by

growing instances of inequality between rich and poor, by the prevalence of a

selfish and individualistic mindset which also finds expression in an

unregulated financial capitalism. In addition to the varied forms of terrorism

and international crime, peace is also endangered by those forms of

fundamentalism and fanaticism which distort the true nature of religion, which

is called to foster fellowship and reconciliation among people.

All the same, the many different efforts at peacemaking which

abound in our world testify to mankind’s innate vocation to peace. In every

person the desire for peace is an essential aspiration which coincides in a

certain way with the desire for a full, happy and successful human life. In

other words, the desire for peace corresponds to a fundamental moral principle,

namely, the duty and right to an integral social and communitarian development,

which is part of God’s plan for mankind. Man is made for the peace which is

God’s gift.

All of this led me to draw inspiration for this Message from the

words of Jesus Christ: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called

children of God” (Mt 5:9).

2. The beatitudes which Jesus proclaimed (cf. Mt 5:3-12

and Lk 6:20-23) are promises. In the biblical tradition, the beatitude is

a literary genre which always involves some good news, a “gospel”, which

culminates in a promise. Therefore, the beatitudes are not only moral

exhortations whose observance foresees in due time – ordinarily in the next life

– a reward or a situation of future happiness. Rather, the blessedness of which

the beatitudes speak consists in the fulfilment of a promise made to all those

who allow themselves to be guided by the requirements of truth, justice and

love. In the eyes of the world, those who trust in God and his promises often

appear naïve or far from reality. Yet Jesus tells them that not only in the next

life, but already in this life, they will discover that they are children of

God, and that God has always been, and ever will be, completely on their side.

They will understand that they are not alone, because he is on the side of those

committed to truth, justice and love. Jesus, the revelation of the Father’s

love, does not hesitate to offer himself in self-sacrifice. Once we accept Jesus

Christ, God and man, we have the joyful experience of an immense gift: the

sharing of God’s own life, the life of grace, the pledge of a fully blessed

existence. Jesus Christ, in particular, grants us true peace, which is born of

the trusting encounter of man with God.

Jesus’ beatitude tells us that peace is both a messianic gift

and the fruit of human effort. In effect, peace presupposes a humanism open to

transcendence. It is the fruit of the reciprocal gift, of a mutual enrichment,

thanks to the gift which has its source in God and enables us to live with

others and for others. The ethics of peace is an ethics of fellowship and

sharing. It is indispensable, then, that the various cultures in our day

overcome forms of anthropology and ethics based on technical and practical

suppositions which are merely subjectivistic and pragmatic, in virtue of which

relationships of coexistence are inspired by criteria of power or profit, means

become ends and vice versa, and culture and education are centred on

instruments, technique and efficiency alone. The precondition for peace is the

dismantling of the dictatorship of relativism and of the supposition of a

completely autonomous morality which precludes acknowledgment of the ineluctable

natural moral law inscribed by God upon the conscience of every man and woman.

Peace is the building up of coexistence in rational and moral terms, based on a

foundation whose measure is not created by man, but rather by God. As Psalm 29

puts it: “May the Lord give strength to his people; may the Lord bless his

people with peace” (v. 11).

Peace: God’s gift and the fruit of human

effort

3. Peace concerns the human person as a whole, and it involves

complete commitment. It is peace with God through a life lived according to his

will. It is interior peace with oneself, and exterior peace with our neighbours

and all creation. Above all, as Blessed John XXIII

wrote in his Encyclical Pacem

in Terris, whose fiftieth anniversary will fall in a few months, it

entails the building up of a coexistence based on truth, freedom, love and

justice.[2] The denial of what makes up the

true nature of human beings in its essential dimensions, its intrinsic capacity

to know the true and the good and, ultimately, to know God himself, jeopardizes

peacemaking. Without the truth about man inscribed by the Creator in the human

heart, freedom and love become debased, and justice loses the ground of its

exercise.

To become authentic peacemakers, it is fundamental to keep in

mind our transcendent dimension and to enter into constant dialogue with God,

the Father of mercy, whereby we implore the redemption achieved for us by his

only-begotten Son. In this way mankind can overcome that progressive dimming and

rejection of peace which is sin in all its forms: selfishness and violence,

greed and the will to power and dominion, intolerance, hatred and unjust

structures.

The attainment of peace depends above all on recognizing that we

are, in God, one human family. This family is structured, as the Encyclical

Pacem

in Terris taught, by interpersonal relations and

institutions supported and animated by a communitarian “we”, which entails an

internal and external moral order in which, in accordance with truth and

justice, reciprocal rights and mutual duties are sincerely recognized. Peace is

an order enlivened and integrated by love, in such a way that we feel the needs

of others as our own, share our goods with others and work throughout the world

for greater communion in spiritual values. It is an order achieved in freedom,

that is, in a way consistent with the dignity of persons who, by their very

nature as rational beings, take responsibility for their own actions.[3]

Peace is not a dream or something utopian; it is possible. Our

gaze needs to go deeper, beneath superficial appearances and phenomena, to

discern a positive reality which exists in human hearts, since every man and

woman has been created in the image of God and is called to grow and contribute

to the building of a new world. God himself, through the incarnation of his Son

and his work of redemption, has entered into history and has brought about a new

creation and a new covenant between God and man (cf. Jer

31:31-34), thus enabling us to have a “new heart” and a “new spirit” (cf.

Ez 36:26).

For this very reason the Church is convinced of the urgency of a

new proclamation of Jesus Christ, the first and fundamental factor of the

integral development of peoples and also of peace. Jesus is indeed our peace,

our justice and our reconciliation (cf. Eph 2:14; 2 Cor 5:18). The

peacemaker, according to Jesus’ beatitude, is the one who seeks the good of the

other, the fullness of good in body and soul, today and tomorrow.

From this teaching one can infer that each person and every

community, whether religious, civil, educational or cultural, is called to work

for peace. Peace is principally the attainment of the common good in society at

its different levels, primary and intermediary, national, international and

global. Precisely for this reason it can be said that the paths which lead to

the attainment of the common good are also the paths that must be followed in

the pursuit of peace.

Peacemakers are those who love, defend and

promote life in its fullness

4. The path to the attainment of the common good and to peace is

above all that of respect for human life in all its many aspects, beginning with

its conception, through its development and up to its natural end. True

peacemakers, then, are those who love, defend and promote human life in all its

dimensions, personal, communitarian and transcendent. Life in its fullness is

the height of peace. Anyone who loves peace cannot tolerate attacks and crimes

against life.

Those who insufficiently value human life and, in consequence,

support among other things the liberalization of abortion, perhaps do not

realize that in this way they are proposing the pursuit of a false peace. The

flight from responsibility, which degrades human persons, and even more so the

killing of a defenceless and innocent being, will never be able to produce

happiness or peace. Indeed how could one claim to bring about peace, the

integral development of peoples or even the protection of the environment

without defending the life of those who are weakest, beginning with the unborn.

Every offence against life, especially at its beginning, inevitably causes

irreparable damage to development, peace and the environment. Neither is it just

to introduce surreptitiously into legislation false rights or freedoms which, on

the basis of a reductive and relativistic view of human beings and the clever

use of ambiguous expressions aimed at promoting a supposed right to abortion and

euthanasia, pose a threat to the fundamental right to life.

There is also a need to acknowledge and promote the natural

structure of marriage as the union of a man and a woman in the face of attempts

to make it juridically equivalent to radically different types of union; such

attempts actually harm and help to destabilize marriage, obscuring its specific

nature and its indispensable role in society.

These principles are not truths of faith, nor are they simply a

corollary of the right to religious freedom. They are inscribed in human nature

itself, accessible to reason and thus common to all humanity. The Church’s

efforts to promote them are not therefore confessional in character, but

addressed to all people, whatever their religious affiliation. Efforts of this

kind are all the more necessary the more these principles are denied or

misunderstood, since this constitutes an offence against the truth of the human

person, with serious harm to justice and peace.

Consequently, another important way of helping to build peace is

for legal systems and the administration of justice to recognize the right to

invoke the principle of conscientious objection in the face of laws or

government measures that offend against human dignity, such as abortion and

euthanasia.

One of the fundamental human rights, also with reference to

international peace, is the right of individuals and communities to religious

freedom. At this stage in history, it is becoming increasingly important to

promote this right not only from the negative point of view, as freedom from

– for example, obligations or limitations involving the freedom to choose

one’s religion – but also from the positive point of view, in its various

expressions, as freedom for – for example, bearing witness to

one’s religion, making its teachings known, engaging in activities in the

educational, benevolent and charitable fields which permit the practice of

religious precepts, and existing and acting as social bodies structured in

accordance with the proper doctrinal principles and institutional ends of each.

Sadly, even in countries of long-standing Christian tradition, instances of

religious intolerance are becoming more numerous, especially in relation to

Christianity and those who simply wear identifying signs of their religion.

Peacemakers must also bear in mind that, in growing sectors of

public opinion, the ideologies of radical liberalism and technocracy are

spreading the conviction that economic growth should be pursued even to the

detriment of the state’s social responsibilities and civil society’s networks of

solidarity, together with social rights and duties. It should be remembered that

these rights and duties are fundamental for the full realization of other rights

and duties, starting with those which are civil and political.

One of the social rights and duties most under threat today is

the right to work. The reason for this is that labour and the rightful

recognition of workers’ juridical status are increasingly undervalued, since

economic development is thought to depend principally on completely free

markets. Labour is thus regarded as a variable dependent on economic and

financial mechanisms. In this regard, I would reaffirm that human dignity and

economic, social and political factors, demand that we continue “to prioritize

the goal of access to steady employment for everyone.”[4] If this ambitious goal is to be realized, one prior

condition is a fresh outlook on work, based on ethical principles and spiritual

values that reinforce the notion of work as a fundamental good for the

individual, for the family and for society. Corresponding to this good are a

duty and a right that demand courageous new policies of universal employment.

Building the good of peace through a new model

of development and economics

5. In many quarters it is now recognized that a new model of

development is needed, as well as a new approach to the economy. Both integral,

sustainable development in solidarity and the common good require a correct

scale of goods and values which can be structured with God as the ultimate point

of reference. It is not enough to have many different means and choices at one’s

disposal, however good these may be. Both the wide variety of goods fostering

development and the presence of a wide range of choices must be employed against

the horizon of a good life, an upright conduct that acknowledges the primacy of

the spiritual and the call to work for the common good. Otherwise they lose

their real value, and end up becoming new idols.

In order to emerge from the present financial and economic

crisis – which has engendered ever greater inequalities – we need people, groups

and institutions which will promote life by fostering human creativity, in order

to draw from the crisis itself an opportunity for discernment and for a new

economic model. The predominant model of recent decades called for seeking

maximum profit and consumption, on the basis of an individualistic and selfish

mindset, aimed at considering individuals solely in terms of their ability to

meet the demands of competitiveness. Yet, from another standpoint, true and

lasting success is attained through the gift of ourselves, our intellectual

abilities and our entrepreneurial skills, since a “liveable” or truly human

economic development requires the principle of gratuitousness as an expression of fraternity and the logic of gift.[5] Concretely, in economic activity,

peacemakers are those who establish bonds of fairness and reciprocity with their

colleagues, workers, clients and consumers. They engage in economic activity for

the sake of the common good and they experience this commitment as something

transcending their self-interest, for the benefit of present and future

generations. Thus they work not only for themselves, but also to ensure for

others a future and a dignified employment.

In the economic sector, states in particular need to articulate

policies of industrial and agricultural development concerned with social

progress and the growth everywhere of constitutional and democratic states. The

creation of ethical structures for currency, financial and commercial markets is

also fundamental and indispensable; these must be stabilized and better

coordinated and controlled so as not to prove harmful to the very poor. With

greater resolve than has hitherto been the case, the concern of peacemakers must

also focus upon the food crisis, which is graver than the financial crisis. The

issue of food security is once more central to the international political

agenda, as a result of interrelated crises, including sudden shifts in the price

of basic foodstuffs, irresponsible behaviour by some economic actors and

insufficient control on the part of governments and the international community.

To face this crisis, peacemakers are called to work together in a spirit of

solidarity, from the local to the international level, with the aim of enabling

farmers, especially in small rural holdings, to carry out their activity in a

dignified and sustainable way from the social, environmental and economic points

of view.

Education for a culture of peace: the role of the

family and institutions

6. I wish to reaffirm forcefully that the various peacemakers

are called to cultivate a passion for the common good of the family and for

social justice, and a commitment to effective social education.

No one should ignore or underestimate the decisive role of the

family, which is the basic cell of society from the demographic, ethical,

pedagogical, economic and political standpoints. The family has a natural

vocation to promote life: it accompanies individuals as they mature and it

encourages mutual growth and enrichment through caring and sharing. The

Christian family in particular serves as a seedbed for personal maturation

according to the standards of divine love. The family is one of the

indispensable social subjects for the achievement of a culture of peace. The

rights of parents and their primary role in the education of their children in

the area of morality and religion must be safeguarded. It is in the family that

peacemakers, tomorrow’s promoters of a culture of life and love, are born and

nurtured.[6]

Religious communities are involved in a special way in this

immense task of education for peace. The Church believes that she shares in this

great responsibility as part of the new evangelization, which is centred on

conversion to the truth and love of Christ and, consequently, the spiritual and

moral rebirth of individuals and societies. Encountering Jesus Christ shapes

peacemakers, committing them to fellowship and to overcoming injustice.

Cultural institutions, schools and universities have a special

mission of peace. They are called to make a notable contribution not only to the

formation of new generations of leaders, but also to the renewal of public

institutions, both national and international. They can also contribute to a

scientific reflection which will ground economic and financial activities on a

solid anthropological and ethical basis. Today’s world, especially the world of

politics, needs to be sustained by fresh thinking and a new cultural synthesis

so as to overcome purely technical approaches and to harmonize the various

political currents with a view to the common good. The latter, seen as an

ensemble of positive interpersonal and institutional relationships at the

service of the integral growth of individuals and groups, is at the basis of all

true education for peace.

A pedagogy for peacemakers

7. In the end, we see clearly the need to propose and promote a

pedagogy of peace. This calls for a rich interior life, clear and valid moral

points of reference, and appropriate attitudes and lifestyles. Acts of

peacemaking converge for the achievement of the common good; they create

interest in peace and cultivate peace. Thoughts, words and gestures of peace

create a mentality and a culture of peace, and a respectful, honest and cordial

atmosphere. There is a need, then, to teach people to love one another, to

cultivate peace and to live with good will rather than mere tolerance. A

fundamental encouragement to this is “to say no to revenge, to recognize

injustices, to accept apologies without looking for them, and finally, to

forgive”,[7] in such a way that mistakes and

offences can be acknowledged in truth, so as to move forward together towards

reconciliation. This requires the growth of a pedagogy of pardon. Evil is in

fact overcome by good, and justice is to be sought in imitating God the Father

who loves all his children (cf. Mt 5:21-48). This is a slow process, for

it presupposes a spiritual evolution, an education in lofty values, a new vision

of human history. There is a need to renounce that false peace promised by the

idols of this world along with the dangers which accompany it, that false peace

which dulls consciences, which leads to self-absorption, to a withered existence

lived in indifference. The pedagogy of peace, on the other hand, implies

activity, compassion, solidarity, courage and perseverance.

Jesus embodied all these attitudes in his own life, even to the

complete gift of himself, even to “losing his life” (cf. Mt 10:39; Lk

17:33; Jn 12:25). He promises his disciples that sooner or later they

will make the extraordinary discovery to which I originally alluded, namely that

God is in the world, the God of Jesus, fully on the side of man. Here I would

recall the prayer asking God to make us instruments of his peace, to be able to

bring his love wherever there is hatred, his mercy wherever there is hurt, and

true faith wherever there is doubt. For our part, let us join Blessed John

XXIII in asking God to enlighten all leaders so that, besides caring

for the proper material welfare of their peoples, they may secure for them the

precious gift of peace, break down the walls which divide them, strengthen the

bonds of mutual love, grow in understanding, and pardon those who have done them

wrong; in this way, by his power and inspiration all the peoples of the earth

will experience fraternity, and the peace for which they long will ever flourish

and reign among them.[8]

With this prayer I express my hope that all will be true

peacemakers, so that the city of man may grow in fraternal harmony, prosperity

and peace.

From the Vatican, 8 December 2012

BENEDICTUS PP XVI

[1] Cf. SECOND

VATICAN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern

World, Gaudium

et Spes, 1.

[2] Cf.

Encyclical Letter Pacem

in Terris (11 April 1963): AAS 55 (1963),

265-266.

[3] Cf.

ibid.: AAS 55 (1963), 266.

[4] BENEDICT

XVI, Encyclical Letter Caritas

in Veritate (29 June 2009), 32: AAS 101 (2009), 666-667.

[5] Cf. ibid,

34 and 36: AAS 101 (2009), 668-670 and 671-672.

[6] Cf. JOHN

PAUL II, Message

for the 1994 World Day of Peace (8 December 1993): AAS 86 (1994),

156-162.

[7] BENEDICT

XVI, Address

at the Meeting with Members of the Government, Institutions of the

Republic, the Diplomatic Corps, Religious Leaders and Representatives of

the World of Culture, Baabda-Lebanon (15 September 2012):

L’Osservatore Romano, 16 September 2012, p. 7.

|

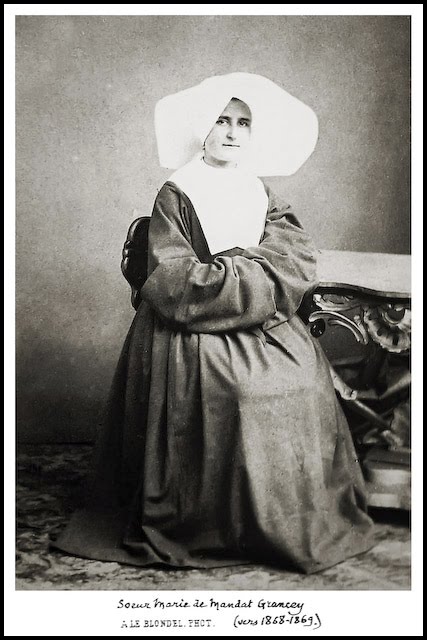

Sr. Marie De Mandat-Grancey Foundation

P.O.Box 275

Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724 USA

P.O.Box 275

Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724 USA

" I am not a priest and cannot bless them, but all that the heart of a mother can ask of God for her children, I ask of Him and will never cease to ask Him." ~ Sister Marie

“The grace of our Lord be with us forever.” ~ Sr. Marie