This post contains segments 11-20 gathered in one post. Please find this post and all other segments listed singularly (including one choice of segments 1-10 gathered in one post) in the left tool bar. Thank you! Please share.

Segment 11

Father John Mary Jung, totally opposed to mysticism, was urged to read Catherine Emmerich’s book and through the Daughters of Charity, had already received a copy.

Ordained in 1875, he also was a teacher and chaplain to the Daughters in Smyrna. Sister Marie and Father Poulin discussed Father Jung and she was convinced he’ s the right man to help seek Mary’s home in Ephesus.

They decided to go during the summer months. That gave them six months to prepare seriously for this experience, to quiet their spirits, to spend time in developing a more mature approach to this consideration.

There were two circumstances that confirmed their decision. 1 – Father John Mary Jung, an old non-commissioned officer, a professor of Holy Scriptures, of Hebrew, of natural sciences, of mathematics and therefore a teacher of science at the College of Sacre Coeur, was also well-known as being the most opposed to everything that concerned mysticism, dreams and visions.

Thus, he was one of the adversaries of Catherine Emmerich and one of the most implacable. He also said, “Girls dreams.” For him, the matter was finished.

“Should I waste my time reading these absurdities?” Father Jung thoroughly examined his conscience. “Am I supposed to sin?” And so on and so on.

As Father Poulin finished reading, the book had captured his attention. He had absorbed all the details and became very much interested, so much so that he held onto the book and took it home to study it and just how he might attack it. That skepticism remained about Catherine Emmerich, her visions and his determination to prove her as that sister with the “girlish dreams.”

Father Poulin had asked his colleague Father Jung to read it. Since Father Jung was chaplain to the Daughters, he already had received a copy of the book. They had politely pushed it off onto him.

Father Jung was still irritated over the book. He actually had more opposition to mysticism than Father Poulin and had absolutely no appreciation for it at all. He believed these were the ravings of a sick, imaginative Anne Catherine Emmerich and felt she had gone a little too far in her attempt to entice Father Poulin into believing in mysticism.

Father Jung was born on Christmas Day, 25 December 1846 in Grosbliderstroff (Moselle) within the limits of Lorraine and Sarre to a profoundly Christian family. One of his brothers followed him into the Congregation, and two of his sisters and three nieces became religious in the Congregation of Providence in Peltre.

He had an excellent memory and was attracted to foreign languages. At an early age, he learned German; his village had a consequential number of Jews who facilitated his learning Hebrew. His father sent him to school in Sarreguemines, then to minor seminary in Montigny-Lez-Metz where his vocation to the priesthood first manifested itself.

In 1865, he attended the major seminary in Metz where serious doubts surfaced about his religious vocation, so he decided to embrace a military career. In the Army, he attained the rank of sergeant.

When the Germans were menacing the frontier with France in 1870, he left Montpellier for combat and was wounded in a field close to his paternal home. He was captured and taken to Saxony where a young German girl proposed to him. However, he refused and told her, “I have nothing of that which would give happiness to a woman.”

After he was liberated from prisoner-of-war status, he returned to France and again felt a call to the religious life. He entered the major seminary at Reims of which the Sulpicians had charge. He was ordained a priest on 22 May 1875.

Subsequently he taught in several places in France before being sent to the French School at Smyrna, an assignment he generously accepted. At Smyrna he taught science and was a most popular teacher among students as well as Greeks, Jews and Muslims. French naval officers in the area also appreciated him.

In the spring of 1891, a porter delivered a packet to Father Jung. He knew it was the book about Sister Anne Catherine Emmerich’s visions. “Thank you. Just put it over there,” he said to the porter, obviously annoyed.

Sister Marie had been a passionate adherent of Catherine Emmerich for a long time and had often said she had been searching for someone who would excavate the vicinities around Ephesus and try to locate the house and Mary’s grave that Catherine Emmerich had mentioned.

Since Father Jung celebrated mass at the French Hospital every day in the morning, Sister Marie had an opportunity to discuss Father Poulin’s discussions with Father Jung which led to her one thought, “I’ve found the right man!”

One morning during breakfast, Sister Marie and Father Jung discussed the matter, but the father, as an unrelenting skeptic, rejected everything. She contested his opinions with all her heart; she truly believed Catherine Emmerich’s visions weren’t nonsense nor so ridiculous as he liked to believe.

“I’ll send you the book,” she said one day. “Do promise me you’ll read it.”

This was the packet the porter delivered. Father Jung still felt he must prove these revelations a hoax, so in order to get rid of Sister Marie, he took the book at nine o’clock in the evening – after prayers – and before going to bed, opened it and started to read. He read the first page; then the second; then the third and finally the whole book right to the last line.

“It’s four o’clock in the morning . . . I’m still reading,” he said to himself.

Like Father Poulin, Father Jung had fallen under the charm of Anne Catherine Emmerich’s story.

Segment 12: The start of conversion of Father Jung.

Segment 12

Father Jung was amazed at Catherine Emmerich’s book and his conversion to belief of her visions at least has started, but there still is a long way to go. Father Poulin is stuck between belief and disbelief mostly because of a lack of proof.

After Father Jung finished the book, his conversation became completely different. “I don’t know,” he said to his brothers of the Confraternity. “I can declare nothing as to the veracity of Catherine Emmerich’s visions, but what greatly surprises me is that I didn’t hesitate to confirm that nothing in these visions contests the Gospel; also, they fit in perfectly with the Holy Scripture and on many points they complement marvelously the silence of the Gospel.

“I don’t understand,” he continued “how a poor country girl, always ill, naïve and ignorant, could find . . . could have said such beautiful, such wise, such strange things if her visions had not been true.”

Father Jung’s conversion over to Catherine Emmerich had started but was far from complete. Then another incident occurred, more important for everyone involved. It happened in February, 1891, before Father Jung read the book sent by Sister Marie. It concerned the intervention of Father Lobry, who came from Constantinople to Smyrna on a private visit.

Father Poulin told him what preoccupied all of them, about Ephesus and the plan to go there during the long summer holiday. Father Lobry, like Father Jung and Father Poulin, was hostile to visionaries and their visions.

“I saw,” he said one day, “miracles at Lourdes. I am ready to confirm they were miracles, however, I don’t believe.”

Father Poulin knew this was Father Lobry’s way of thinking and his disposition, but he had no idea how Father Lobry became interested in this question of Ephesus. And after twelve years, it remained a mystery to Father Poulin. The important thing is that Father Lobry agreed with Father Poulin’s group and supported the researches they were about to undertake.

Father Lobry looked at Father Poulin and then at Father Jung. “Here, take this,” Father Lobry said. “Here are fifty Francs for your journey,” and he counted out the Francs and handed them to Father Jung.

With great surprise, Father Poulin watched the proceedings. “I could see,” he said. “I could hear, but I could not believe my eyes or my ears.”

So this question arose for Father Poulin when he heard Father Lobry speak in such a way: Did he believe Catherine Emmerich? Despite being an admirer and believer of Catherine Emmerich – although still a skeptic – Father Poulin was overwhelmed by his friend’s actions.

“I am in this troubled condition between belief and disbelief,” Father Poulin reasoned to himself, “but common sense refuses resolutely to accept it because substantial and convincing proof is missing.”

Segment 13:Father Jung swings into action to search for Mary’s home in Ephesus.

Segment 13

Father Jung begins to select members of his archaeological crew, but as it turns out, Father Julien Gouyet, a French clergymen, becomes the first to find the Blessed Virgin Mary’s home through the visions of Anne Catherine Emmerich, but encountered a problem.

A quiet excitement began to overtake Sister Marie and the other Daughters as they took the matter of Mary’s home in Ephesus to prayer.

Father Jung had been on other excursions so he was named leader of this hunt. He selected Father Vervault, a Lazarist on holiday from Santorin House at Smyrna and a very much interested Vincentian, to participate; he picked a man named Thomaso, a servant of the college, to be their servant; and a man named Mr. Pelecas, a friend of Father Jung’s and free employee of the railway, to record the hunt.

In Ephesus, they engaged a large Black Muslim hunter well-acquainted with the area. For their protection, Mustapha carried a large rifle visible to everyone. He was a hunter by necessity, knew the mountain well enough to be their guide and they trusted him to also protect them from the evil doings and robbers that were in the mountain country.

Father Poulin had classes and didn’t join this team. Still, he would oversee the hunt and insisted that it be conducted in a most orderly, scholarly way so everyone could put this matter of Catherine Emmerich to rest.

Even before she came to the Middle East, Sister Marie had grown interested in the writings of Sister Anne Catherine, the German Augustinian nun, visionary and stigmatist. Her visions had been recorded by Clemens von Brentano, a German romantic poet. Brentano had published a series of books later and in particular, Anne Catherine’s work, The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Sister Marie had read her work and became convinced that in-depth detail with which Anne Catherine had seen the Blessed Virgin’s life and death was authentic. Sister Marie believed that the visions of Our Lady’s last home that Anne Catherine declared was in Ephesus, Turkey, still existed and in fact, needed to be found and secured for pilgrimage.

Anne Catherine Emmerich was born on 8 September 1774 in a farm house at

Flamschen, a farming community at Coesfield in the Diocese of Munster, Westphalia, Germany. Her parents were poor and at age twelve, she was bound out to a farmer. She entered the Augustinian convent at age twenty-eight in 1802 at Agnetenberg, Dulmen where her sisters believed she had received supernatural favors. This was due to multiple ecstasies she appeared to experience.

In 1813, she was confined to bed and stigmata reported on her body. An Episcopal commission investigated and was reportedly convinced of the genuineness of the stigmata.

Five years later, Anne Catherine said that God had answered her prayer to be

relieved of the stigmata and the wounds in her hands and feet closed. The others remained and on Good Friday, all were wont to reopen.

Clemens Brentano was induced to visit her at the time of her second examination in 1819, and to the famous poet’s great amazement, she recognized him.

Anne Catherine died in 1824 at Dulmen, but Brentano recorded her visions that filled forty volumes with detailed scenes and passages from the New Testament and the Life of the Virgin Mary.

The first process of her beatification began in 1892, but was delayed on several occasions because of concerns about historical and theological errors contained in the books published by Brentano. The process was suspended in 1928, but reopened again in 1973 and finally on 3 October 2004, Anne Catherine Emmerich was beatified by Pope John Paul II.

Sister Marie reread with her companions Anne Catherine’s descriptions and felt a powerful desire to see the visible evidence of the house that, according to the blessed German nun, Mary had occupied, and to contribute to the discovery of her tomb that one day must be found.

Legend has it, and it’s a strong probability, that John and Mary had come to Ephesus, the largest city in the Roman Empire, its greatest financial center, and that it had a mixture of various cultures of people.

St. Jerome (347-419) wrote about the geography of Jerusalem of the fourth century, but didn’t make any mention of a grave belonging to Mary, or of a monument built on her grave in Jerusalem or its vicinity. In St. Jerome’s lifetime, the only church dedicated to Mary was in Ephesus.

“After completing her third year here (in Ephesus), Mary had a great desire to go to Jerusalem. John and Peter took her there. She became very ill and lost so much weight in Jerusalem that everybody thought she would die so they prepared a grave for her. When it was finished, the Virgin Mary recovered and returned to Ephesus.

“The Virgin Mary became very weak after she returned, and at sixty-four years of age, she died. The saints around her performed a funeral ceremony and put the coffin they had specially prepared into a cave about two kilometers away from the house.”

Anne Catherine said at this point in her vision that St. Thomas came there after Mary’s death and cried with sorrow because he had not been able to arrive in time. So his friends, not wanting to hurt his feelings, took him to the cave.

Anne Catherine continued: “When they came to the cave they prostrated themselves. Thomas and his friends walked impatiently to the door. St. John followed them. After they removed the bushes at the entrance of the cave, two of them went inside and kneeled in front of the grave. John neared the coffin, unlaced its ties, opened the lid and when they all approached it, they were stunned: Mary’s corpse was no longer in the shroud. But the shroud had remained intact. After this event, the mouth of the cave that contained the grave was closed and the house turned into a chapel.”

A French clergyman named Julien Gouyet had read Brentano’s book The Life of the Virgin Mary back in 1880, and Anne Catherine’s revelations. He tried to prove them by his writings but was unsuccessful, so he decided to go to Ephesus to see if the house said to belong to Mary fit the description in the book.

Upon his arrival in Ephesus, Father Gouyet questioned people who lived in villages around the area. He obtained information in Kirkindje where people were genuine descendents of the seven families that fell into slavery after the seizure of Ephesus by the Turks. It was they who gave the name of Panaghia Capouli (Door of the Virgin) to the house of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

According to the citizens, tradition held that after the crucifixion of Jesus, the Blessed Virgin Mary came to Ephesus with John. She hid in a cave named Kriphti Panaghia (in Greek, hidden virgin), then in Kavakli Panaghia. Still later, she moved toward the west on the Mount Bulbul-daga (in Turkish, mount of the Nightingale) where she lived until her death.

When Father Gouyet got to Ephesus, he discovered that Anne Catherine Emmerich’s descriptions to be exact to an astonishing degree. He was the first to discover the ruins of the Blessed Virgin Mary’s home in Ephesus. Gouyet believed the house belonged to the Virgin Mary, sent his related reports to Archbishop Andre Timoni, to the diocesan authorities of Paris and even to Rome. But he did not receive the attention he had expected. No one believed them.

Segment 14: Father Jung's first excursion doesn't work out but the second one becomes more productive

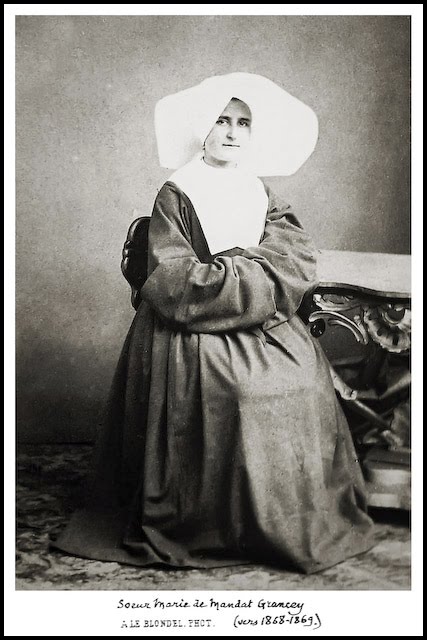

Sister Marie

Segment 14

Father Jung’s first expedition ends in failure, but two days later, they started again and this time, thanks to some women working in a tobacco field, they were led on to water and success on Nightingale Mountain. Opinions of Sister Emmerich’s visions then changed.

Father Jung and his small archaeology group began their hunt on 27 July 1891, a very hot, humid day, and carried their provisions along the old Jerusalem road. They really didn’t believe in Anne Catherine’s revelations, so they could search without much help from the Sisters. They searched most of the day, but finally decided they had lost their route, turned around and headed back home.

Father Jung’s idea was the same as Father Poulin, to scientifically prove that Sister Anne Catherine’s revelations were a mistake, “the dreams of a sick woman.”

On 29 July, they started out again on their second excursion, another hot, sticky, humid day. This time, they used a compass and copy of the revelations given to Sister Anne Catherine. They followed her directions and discovered a path they previously had missed on the first trip. It led them towards the top of Nightingale Mountain.

After they had followed the path a short way up the mountain they found a small hut referred to as a monastery. Inside were two monks so they began to talk with them.

Finally one of the priests asked the monks, “Where did the Blessed Virgin Mary die?”

“In Jerusalem,” the one monk answered. His response pleased the priests. It didn’t fit the Ephesus legend or Anne Catherine’s revelations and probably gave much greater hope to those who were opposed to her mysticism, which included Fathers Jung and Poulin.

They finished their talk with the monks and resumed their climb up Nightingale Mountain. It still was hot and the terrain so rugged that one of the priests had to be carried part of the way. It would take them eleven hours to reach the top.

Exhausted, breathing hard and about to give up the search when they neared the top, they shouted to some women working in a small tobacco field on a plateau. “Nero! Nero! (Water! Water!).”

One of the women stopped and looked at them. “We have no water here,” she said, “but ten minutes farther up the mountain there’s a spring of water near the monastery by some trees.”

They rested a few minutes then started the climb again. When they found the water, they fell to the ground and began to drink. They stopped a few moments to catch their breaths, drank some more, rested, and finally began to relax.

After a while, Father Jung decided to explore the area. He followed the stream for a ways and finally called attention to the others. He pointed out that the stream ran through some trees and up ahead were some stone ruins of a house – four walls and no roof.

It was strange, the one of the other men thought, an artesian spring on top of the mountain. How could that be?

Then one of the others recalled that Mary was supposed to have been the only one who had a stone house on the mountain.

Sister Anne Catherine had said in her revelations that from the top of the mountain one can see Ephesus, the Aegean Sea and the islands of Samos, that the house was made of stone and that it was round and octagonal.

It struck them all at about the same time, Father Jung hurried the rest of the way up the mountain.

Another shouted, “Can you see Ephesus?”

“Yes,” Father Jung answered.

The other called out again. “Can you see the sea?”

“Yes,” came his reply.

“Can you see the island?”

“Yes.”

Suddenly no one was exhausted. They forgot their unbelief. It was just like Anne Catherine Emmerich’s revelations had said. There was only one place on Nightingale Mountain where you could stand and see to the northeast the Ephesus plain, Ayasoulouk and the ruins of the city of Prion; the vast expanse of the Aegean Sea spread out before Father Jung to the west and southwest; and Samos islands, with their numerous peaks, were there in the middle of the waves.

They checked all the other nearby hilltops, but they found no other place from which Ephesus, the sea and the islands could be seen. Now they were convinced, they had found Mary’s house.

Father Jung was so moved by his discovery that he was certain Mary’s grave must be somewhere near here, maybe only a few steps farther.

They stayed two more days to study a great part of the mountain and recorded everything they could see and examine. They learned from the women that the people called these ruins Panaghia Capouli – the Door of the Virgin.

When the first exploration was finished, Father Jung completely changed his ideas. He returned to Smyrna convinced that Sister Anne Catherine spoke the truth. Panaghia Capouli didn’t have a stronger defender than Father Jung with the possible exception of his superior, Father Poulin.

This was written in part in the Daily Journal (Ephemerides) of the Congregation and Mission and the Daughters of Charity for 29 July 1891, page 298:

“Panaghia Capouli is a small region situated not far from Ephesus. Catherine Emmerich, in her life of the Virgin Mary, tells that the Mother of God lived there in a house built for her by Saint John. She delved into the most minute and most precise details, not only in regard to the house itself, but the surrounding countryside, the site and its orientation, the distances, etc., etc. The missionaries of the House at Smyrna, after they discussed the value of these revelations, decided to make an expedition on site to reach a conclusion, one way or the other. Those who opposed led the works.

After laborious research, they found a ruin, dating from the first centuries, according to the archaeologists, at the place indicated by the visionary, near an ancient chateau. Everything conformed to the description, down to the smallest detail. These observations caused our confreres to have recourse to ecclesiastical authority. The Archbishop of Smyrna named a commission which made a report signed by the Archbishop and whose conclusion is this: “Having good reasons, on the one hand, to believe that the revelations of Catherine Emmerich merit, at least, some credibility, given the homage paid her good faith and to her virtue by her superiors and her contemporaries; noting, on the other hand, book in hand and with our own eyes, the perfect conformity that exists between the ruins that we have visited and that which the visionary describes of the house of the Holy Virgin at Ephesus; knowing still further that local traditions affirm in a positive manner that the Holy Virgin lived in this area, we are strongly inclined to believe that the ruins of Panaghia are truly the remains of the house inhabited by the Holy Virgin.” (Extract of a booklet).”

Segment 15: The archaeological group plans to rest, then return to obtain more proof.

Segment 15

Father Jung’s archaeological team relaxed for two weeks, scheduled another trip and then returned to obtain scientific proof of their finding of Mary’s house. On the third day Father Jung celebrated the first Mass at Panaghia Capouli.

Gregory of Tours (538-594) in The Book of Miracles, a work in which history and legend are sometimes intimately mixed, was the first ecclesiastical writer to speak of a chapel situated on a mountain near Ephesus. He stated, “On the summit of a mountain near Ephesus there are four walls without a roof. John lived within these walls.”

The people of Kirkince (now Sirince), a village about 17 kilometers from Meryem Ana, traditionally believed there had been a house on Bulbul-Dagi (Nightingale Hill) where Mary had lived. Every year on Assumption Day they made a pilgrimage to Panaya Kapulu (Chapel of the All Holy), now Meryem Ana Evi. They believed that Mary was raised up to heaven from this place. This may have seemed strange that a group of Orthodox villagers should believe this when the rest of their church had believed since the Middle Ages that she spent her last days in Jerusalem.

The next two weeks, the archaeology team rested and discussed the next steps in their amazing discovery of Mary’s house. They were eager to go deeper into their findings and set 12 August for their next trip. This time Fathers Poulin and Jung would be included along with four others. They determined it would be most inappropriate to publicize their finds now. At this time, it had to be their secret; there had to be scientific proof.

They also remembered those ten years earlier, when Father Julian Gouyet came through here with the same idea. He said he had found what he believed was the remains of Mary’s Home. The whole matter had been dropped with “subtle insistence” because there was such a great veneration for her home to have been in Jerusalem.

Father Poulin kept a critical account of the findings. He knew that when it was published it would be most provocative. To specifically record and verify all their findings and possibly learn new ones, the trip was made from 19-25 August 1891. On 23 August 1891 the first Mass was celebrated on the Altar of Mary’s House (Panaghia). This was during the third expedition. Father Jung led the group; with him were Fathers Borrel, Paul d’Andria, Heroguer, and non-priests Pelecas and Constinin. On the round massif of the sanctuary, Andreas (an acquaintance of Pelecas living on the mountain) made a shaky table out of three old wooden shelves. On this altar, Father Jung celebrated Mass in Latin, the first Mass at the site of Mary’s Home, the Panaghia Capouli.

Afterwards, they drew maps, did sketches, took pictures and recorded each of their endeavors. There was just one major difficulty: According to Sister Anne Catherine’s revelations, the house was supposed to be octagonal. But from the back it looked round and yet somewhat octagonal. It took them three more years to dig deeper and after they uncovered in depth about a yard of dirt, they found a perfectly octagonal figure on which the original structure had been built.

Again, it was just as Anne Catherine had said. They took all the dimensions of the Home as they found it, its individual rooms, the changes made within the Home, the distances to the sea and to Ephesus, the height of the mountain, and everything they could measure, they recorded. The house had an aura of holiness and peace that affected them all.

The distance from Panaghia Capouli to the sea is four kilometers in a direct line. Altitude is 610 meters. One can see Samos. There was no longer any doubt possible. This was, indeed, the house described by the visionary.

The Vincentian fathers had taken pictures on this occasion and published everything later in their 1896 book “Panaghia or the House of the Blessed Virgin Mary Near Ephesus.”

More compelling evidence that the early church affirmed Mary’s place at Ephesus lies in the fact that the Third Ecumenical Council of the Catholic Church was held in Ephesus (AD 431).

“This council, which met in a large cathedral known as the Double Church of St. Mary, was primarily called to formalize the doctrine known as ‘Theotokos,’ Greek for ‘Mary, Mother of God.’

To name a church after a Saint, according to Canon Law at that time, required that person to actually live or die in the vicinity.

Furthermore, coincidence alone would not have sufficed to decide to hold a Council in Ephesus to define a doctrine concerning Mary as the Mother of God.

Benedict XIV, an outstanding scholar, in his treatise on the Feast of Good Friday and in his treatise on the Feast of the Assumption wrote:

“John amply fulfilled Christ’s orders; in every way he forever cared for Mary with a sense of duty; he had her live with him while he remained in Palestine, and took Her with him when he departed for Ephesus where the Blessed Mother at length proceeded from this life into Heaven.” He went further by stating that “this is the opinion of the Church Universal.”

Segment 16: Sister Marie and Fathers Poulin and Jung discuss purchasing Panaghia.

Segment 16

Priests determine that they must have Panaghia and Sister Marie agreed and said, “Let’s buy it!”The purchase also would be put in her name. Father Poulin believed that the Lord placed Sister Marie in position to buy the site.

Sister Marie listened to the reports that agreed with the revelations of Sister Anne Catherine and her heart burst with excitement. Her prayers had been answered. She quickly and quietly wrote to Father Fiat, the Superior General of the Daughters of Charity, in Rome to request permission to purchase, with her own personal funds, the property on which Mary’s Home was located. In his letter dated 28 October 1891, he gave Sister Marie permission to buy Panaghia.

Father Fiat’s permission was a complete change of stance and fell in line with Father Poulin’s and Father Jung’s ideas, that this truly was the house of the Blessed Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist.

A little later the priests spoke to Sister Marie about the necessity to protect their work and procure ownership of the site. They deemed it absolutely necessary. Some said, “How good it would be if we had that.” Later, they said “We should have this!” Then they said “We must have this!”

The idea made its way into their spirits. But could they buy it? Father Poulin wrote that they couldn’t think about it with this enormous debt of 300-400 thousand francs and with a return of zero. Otherwise, Paris would never permit a similar acquisition. To whom would they turn? The answer was not long in coming to them.

Sister Marie couldn’t have agreed more. For years, she had been thinking about the Blessed Virgin’s grave, looked forward to its discovery and when she had been told about the opportunity to buy Panaghia, her heart was full of joy and she said, “Do . . . let’s buy it.” She knew very well that she would have the funds available to her to make the purchase.

“In whose name should it be?” they asked. “In the name of the Superior General, or the name of the Superior of Smyrna?”

“In my name,” she said firmly. She had the right to claim it and have active participation in the development of the site. They had no doubt that she would

somehow cover the costs.

Later, Father Poulin would write, “The Lord, who sees and organizes things, had taken care to put before us a soul in love with beauty and goodness, who was ready to give herself to everything good, a great soul, devoted, ardent, pious and generous; the noble Sister Marie de Mandat-Grancey. She was, God has chosen her to be, the terrestrial Providence, like Panaghia’s Mother! For twelve years she has been charged of this valiant religious enterprise; she has never failed.”

To have the good fortune to meet Sister Marie and to see the humility hidden under her noble pride, the shout of “in my name” does not come as a surprise. She should be permitted to feel great satisfaction to think she could give her family name to the blessed spot from where the Holy Virgin – and she had no doubt about this – was taken up to Heaven.

After a few years, she would demand and insist that a transfer be made to ensure as much as possible the future of Panaghia. So it was decided to be done in the name of Father Poulin, Superior of the Church of the Sacred Heart. After many difficulties, on May 11, 1910, the new title was obtained and was so well done that a last will of Father Poulin allowed his successor to recover the property that would be confiscated during World War I.

“It is well understood,” Father Poulin stated “that Sister Grancey remains Mistress and Superior of Panaghia as before the transfer, the said transfer having for its goal only to assure the property after her death and not to take it from her.”

Segment 17: Purchase of Panaghia wouldn’t be easy, and they didn’t know who owned it.

Segment 17

A young man with a fez, Mr. Binson, joins Fathers Poulin and Jung on the train to Ephesus and he provides the answer to a major question, who owns the property they want to purchase on Nightingale Mountain.

It was not an easy task to purchase land in Turkey, especially at that time. Plus, they had no idea who owned the property on Nightingale Mountain. And a Catholic in a Turkish country? A nun, as they say, buying from a Muslim? Most agreed that she’d need divine intervention for help, or at least assistance from the Blessed Virgin Mary, to do that. But with Sister Marie, it seemed like supernatural intervention, indeed, came upon her request.

Fathers Poulin and Jung and a Mr. Binson left for Ephesus by train on Wednesday, 27 January 1892. Another young man with a fez joined them in the fourth seat of their compartment. He had a kindly face, a Greek perhaps.

“Uh oh, bad luck,” Father Poulin thought. “We can’t speak about our business . . . a wasted journey.”

Immediately Mr. Binson, who could speak the man’s language, offered him a cigarette.

“How far are you going,” Mr. Binson asked to open a conversation.

“Scala Nova,” the man with the fez answered.

That was exactly where Fathers Poulin and Jung and Mr. Binson were headed. But they didn’t volunteer their destination and kept that information strictly to themselves. They were going there to search for records of ownership of Nightingale Mountain where their precious site was located. But they didn’t dare tell the man with the fez.

Without a prompt, the man with the fez launched into the latest news out of Scala Nova, that there was a scandal about a prominent family and it was the talk of the town. An aging Turk, the Bey of Avaria, had been quite wealthy and owned half of Ephesus. The other half, he said, belonged to the Bey’s nephew who had squandered it. He had borrowed heavily from his uncle and everyone else.

Fortunately, the man with the fez said, he still owned some land. For that reason, The Bey brought a suit against his nephew.

As the conversation continued, Mr. Binson learned that the land the man with the fez talked about was located on Nightingale Mountain, that it actually included the property on which Panaghia Kapuli was located. Both the Bey and the nephew were now in need of money and no one had any idea about how the suit would be settled.

The train pulled into Scala Nova and Fathers Poulin and Jung and Mr. Binson disembarked. They went directly to The Bey. God had given them the answer they needed – who owned the site at Nightingale Mountain.

The Bey graciously welcomed the two professors and Mr. Binson and they talked at great length. Then The Bey insisted that they stay for dinner.

“Providence knew I’d have guests for lunch today,” he said “and inspired my friend to bring me this fish.”

After the meal, they again turned their conversation to business, but The Bey told them he couldn’t possibly sell the property now, that they’d have to come back in two weeks. They settled on returning on Wednesday, 11 February, the Feast of Our Lady of Lourdes. But on that day The Bey said he was still unable to sell, so he invited them back the following week.

Since the two priests had to return to classes, Mr. Binson returned alone. After he met with The Bey, Binson said that The Bey wants to sell, but because of the mortgage held against the nephew, it could not be sold just yet. So they had to wait a while longer.

Segment 18: Sister Marie prepares for the purchase of Panaghia but still doubt looms about authenticity of the site.

Segment 18

Sister Marie makes a deposit in the bank for the purchase of Panaghia while everyone waited for Mr. Binson to learn the results of The Bey’s suit; and Father Louis Duchesne disputes the visions of Anne Catherine Emmerich.

Doubt still clouded the discovery of Mary’s Home on Nightingale Mountain. This was evidenced by a letter sent from Father Duchesne to Rev. Fiat, Superior General of the Lazarists, on 5 February 1892. Father Duchesne wrote:

“It is my duty, I believe, to call your attention to the recent discoveries which took place close to Ephesus and to the incredible state of mind in which your brothers there seem to find themselves. One of them, Fr. Poulin (if I read correctly his signature), is consulting me on this matter. I am answering him in unfavorable, but general terms.

“At first sight, it seems to me extremely imprudent to use the revelations of Anne-Catherine Emmerich as these gentlemen do. These revelations are the products of a sure imposture, in which, however, it would be advisable to make a large allowance for suggestions and unconsciousness. To introduce such elements into the area of tradition and archaeology is to err in the most grievous way. If publicity should come about, you will see the sarcasms that will befall the Lazarists of Smyrna. However, it would be very regrettable that the esteem these gentlemen enjoy would be undermined. They represent France and Catholicism in such a dignified way, in the East, that we could never care enough for their reputation.

“I am available, Most Reverend Father Fiat, to provide you with more information, should you wish to ask me.”

Sister Marie, meanwhile, was hard at work on her own. On 27 February 1892, she deposited a check for 45,000 francs into a special account in the Smyrna branch of the Credit Lyonnaise Bank. The account was established for the purchase of the property in question.

One of Father Poulin’s colleagues, G. Dumont, enjoyed his stay in Paris, not to dispute with Louis Duchesne, but to transcribe the texts of the Fathers and of the historians concerning the question at hand, whether Mary lived her last years in Jerusalem or Ephesus. From the Documents amassed in Paris by Dumont, Father Poulin wrote, and from those that we have been able to find in Smyrna, five things seem to jump out:

1. No known authentic authority for Jerusalem before the sixth century;

2. The first Fathers who spoke of Gethsemane do it in a hesitating manner and do not rely upon the apocrypha;

3. For Ephesus -- (and frankly) the best authors of the 17th and 18th centuries;

4. The most recent historians are divided; half for Jerusalem, half for Ephesus, or they are happy to mention the two opinions without taking sides;

5. Of this whole, one conclusion can be made; Ephesus balances Jerusalem and threatens to replace it.

This result, Father Poulin wrote, was obtained in 1892, five years before the brochure “Ephesus or Jerusalem,” and 14 years before the monumental work of Johann Niessen (1906). We do only want to put in doubt number 4 on the half and half divide of the two opinions, which is almost impossible to verify, and which has no importance since it is not their quantity that counts, but their quality. We have transcribed this result with all the more satisfaction because it synthesizes perfectly the studies that we ourselves have conducted over the years.

Then on 4 March 1893, he wrote to one of his colleagues from Paris, Amedee Allou:

“Do not believe that we have blindly jumped into this affair of Panaghia. I see with a calm eye the obstacles that men and things could throw in its path. The rock has detached from the mountain, but that does not stop it from rolling on.” (Cited in “Ephesus or Jerusalem.”)

Segment 19: Purchase of Panaghia is finally completed.

Sister Marie

Segment 19

At first, it seemed the purchase had been lost, but Mr. Binson’s works it out to finish it. Then the property on Nightingale Mountain is put in Sister Marie’s name and she uses her own resources to restore the area.

Now they were all waiting for completion of the lawsuit made by The Bey against his nephew. On 20 October, they learned the transactions were under way.

However, some days later when all seemed to be concluded, an obstacle appeared. Despite Mr. Binson’s coolness and ability, he thought, “We have lost.” But he regained his optimism and started the proceedings again. He paid some money and then was back in control of the situation.

The good news finally came to Father Poulin at Sacre Coeur in a telegram on 15 November at 5:40 in the evening. It read, “Congratulations, business concluded. Binson.”

When the deal was finally finished, it had cost less than 31,000 francs in French money.

What a valuable piece of property this Panaghia, by no means a small piece of land. Its length stretched two kilometers from east to west and its width 1300 meters. Its total area is 27½ acres. It takes three hours to cross the plain, five hours with the mountains and the hollows.

When the land was bought, it had been agreed to put everything together for their research: the Castle, the Terrace of Kara-Kaya; Bulbul-Dagh; Kara-Tchalty and the Tower of a Hundred Guards; also the Grotto which is below, known as the Cave of Latone.

As Sister Marie instructed, the property was registered in her name.

“It was logical,” Father Poulin wrote. “She had borne all the expenses and still does for Panaghia; repairing roads, construction of buildings, maintenance of the chapel, amelioration of the property, planting trees, annual expenses for excavations. She has done this with endless generosity and good will.”

“Do make use of me while I am here,” she had repeated often. “After my death, I will not be able to help you.

But Mary’s home was neglected for a long time, had been terribly damaged, looted and uninhabited. Now, however, Sister Marie held the legal title to the land and she knew it was her responsibility to restore Mary’s home. She also knew that people would want to come and see for themselves just how Mary’s Home actually had looked when she lived there.

This, however, was Turkey. Bureaucratic details were held in abeyance and it dragged on and on. It tested the mettle of Sister Marie and her devotion to the members. She managed to have a small building built on the property for a caretaker who was a devout Muslim. Her emotions fluctuated – joy, satisfaction, sorrow, gratitude, determination, thanks, frustration – with the pressures her team had to endure. The reality of it all wouldn’t take effect it until she and her sisters actually viewed the home on December 12, 1892. That day was their first visit to Mary’s home.

Sister Marie, also an administrator, began to discuss with the men their immediate needs for the project. She wanted to construct the following year (1893) a chalet where equipment and tools could be stored and where the sisters would have necessary accommodations. At times, it also could be used for pilgrims to remain overnight.

On 1 December 1892, fifteen days after its purchase, great consolation came to Sister Marie. Archbishop Timoni of Smyrna and Vicar Apostolic of Asia Minor arrived with a twelve-member commission to make an official visitation of Panaghia Capouli. The smallest details of the find were compared with the revelations of Sister Anne Catherine Emmerich. Their official record was made, ratified and signed by the commission, and received most favorable recognition. The commission’s report was followed by the local civil and ecclesiastical approval.

As the RECORD OF EVIDENCE, here in detail is what Archbishop Timoni and his group certified and attested to:

Recent research, undertaken in accordance with the indications of Sister Anne Catherine Emmerich, has seriously drawn the attention of the nation for some six months toward an area close to Ephesus and called Panaghia-Capouli (Door of the Virgin). We wanted to verify for ourselves the exactitude of the report that was given us. To this end, on Thursday, December 1, 1892, we were transported to said area of Panaghia-Capouli. There we found the ruins, well enough preserved, of an old house or chapel whose construction according to a competent archeologist dates from the first century of our era and which, as much for the location as for the interior plan, corresponds clearly and entirely to that which Catherine Emmerich said in her revelations regarding the house of the Holy Virgin at Ephesus.

Segment 20:Excavagation begins and more findings are discovered.

Segment 20

Sister Marie believes the Blessed Mother had selected her for this special mission. It was decided to start the excavations and more surprises were unearthed by workers and hoped to find the burial place for Mary.

As an aristocratic young lady, Sister Marie knew manners and courtesies. She was comfortable around the very wealthy, the highly educated, the finely polished and determined. Most of all, she was very compassionate with the needy and the suffering. She had observed and assisted her mother, the Countess, in the preparations for entertaining officials of church and state. She gained further lessons of etiquette at Rue du Bac for handling crowds of pilgrims from all parts of the world as well as for those dearly beloved bashful needy noble people who stood in want of compassion.

As a Daughter of Charity, her first service was to God, then to the Blessed Mother. As a daughter, she retained any inheritance and personal funds given her which she was to use in works of faith and charity. Over the years, she had responded generously according to the rules of the Little Company of Charity, and her heart was most generous as attested to by those with whom she lived. Sister Marie believed the Blessed Mother had selected her for this particular mission.

Our Lady chose wisely, knew that the generosity of Sister Marie had already helped spread devotion to her as the Immaculate Virgin Mary, Mother of God and Mother of Man. Sister Marie, indeed, had made her first deposit on Mary’s project.

Workers and the sisters were all well aware of a need for improved travel from Smyrna to Panaghia Capouli. Tools, equipment and supplies had to be transported by pack animals over treacherous ground. The journey had to be eased and quickened for the workmen. Thus the construction of the twenty-mile roadway over rugged mountainous terrain offered a great challenge and demanded cash. Sister Marie was up to paying for this, too.

To ready the excavations of the Home, in July 1894 the workers decided to level the ground behind it for erection of a building to store equipment and to house the Sisters who might have to stay overnight. It would give protection and rest for workers as needed. The preparatory work of hand-grading it, however, delayed the building project for three years.

Then they unsuspectingly stumbled upon two tombs. The heads of the skeletons faced Mary’s Home. They judged that the tombs dated back to the fourth century. Many funeral objects were also found. Among them were civic medals, funeral lamps and even a terra-cotta mold for making Eucharistic hosts bearing liturgical symbols of wheat and grapes. It was obvious that a Christian service had been associated with Mary’s Home.

After they found this secret place, real hope began to surface that they would also stumble upon the Tomb of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The four hired workers were eager to search various spots on the mountain. They trusted that they would come upon the prized tomb as narrated by Sister Anne Catherine Emmerich. Despite their great efforts, Mary’s Tomb was never found, and two of the men died during this period of work.

Then on 23 August, the workmen dug five feet deeper behind the chapel of Mary’s Home and found a greater surprise. There was a turn, or bend in the foundation that indicated it was a part of an octagonal frame. It coincided with the description by Sister Anne Catherine. They had discovered the octagonal base of Mary’s Home.

As they dug down through the floor, they came upon the greatest find of all: another cache of broken blackened pieces of marble, some ashes which had coagulated with soot and soil along with some pieces of broken stone. At first they didn’t understand, but after studying the find, they concluded they were in the middle of Mary’s Home and had come across the old fireplace. They and all who were part of this archaeological project believed their conclusion was correct. They treated these remains with respect, asked for and received many extraordinary favors in their prayers. Mary, they said, was granting the grace of miracles just as she did at Rue du Bac when she invited all to come to the altar and ask for graces from her.

The archaeological search consumed the interest of the workers, and they delayed all their earlier plans. So it was not until 1903, after a wait of twenty years, that they finally erected the building long planned as a shelter for the sisters.

The twenty-mile road also was serving its purpose. Panaghia Capouli was finally getting some publicity. Pilgrims and archaeologists were motivated to come and see Mary’s Home.

Sister Marie also was compelled to collect some of the scattered stones with Hebrew engravings and she reestablished the Stations of the Cross which Mary, according to Sister Anne Catherine’s revelations, had dutifully measured and placed in a setting adjacent to her Home. Like Mary, she too often made the Stations of the Cross while working on the grounds and the buildings for the pilgrims.

Segment 21: Development of Panaghi Capouli begins and a surprise for Sister Marie.

Sr. Marie De Mandat-Grancey Foundation

P.O.Box 275

Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724 USA

P.O.Box 275

Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724 USA

" I am not a priest and cannot bless them, but all that the heart of a mother can ask of God for her children, I ask of Him and will never cease to ask Him." ~ Sister Marie

“The grace of our Lord be with us forever.” ~ Sr. Marie