For your convenience are gathered here below Segments 1-10. I will periodically add the up-to-date Segments in one post.

Segment 1

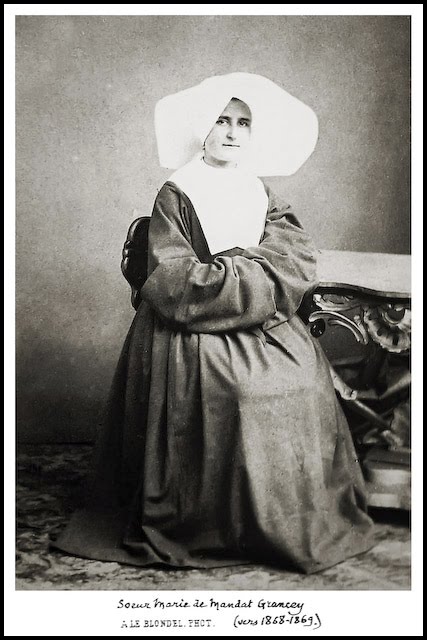

Introduction: This is the first of a series of brief segments about Sister Marie de Mandat-Grancey, who decided at a young age to become a Daughter of Charity, a servant to the poor and a teacher. But later she was responsible for the discovery of the Blessed Virgin Mary’s home that John, an Apostle of Jesus Christ, built for her on Nightingale Mountain near Ephesus, Asia Minor, now Turkey after crucifixion of Jesus.

The call of God, the cry of the poor

She watched the tattered, ragged, unkempt and unemployed people line up daily to seek assistance from the women who wore the big white cornets, universally recognized as the symbol of the charity they practiced. These daughters’ religious habits were akin to the clothing of a country girl from one of the French provinces. Of course, they were the Daughters of Charity that St. Vincent de Paul and St. Louise de Marillac founded in 1633. These were their work clothes; they wore the same ones for religious services.

Vincent and Louise had been touched by the misery that surrounded them in seventeenth-century Paris. Their response -- to assist somehow to alleviate this misery so they organized young women to serve the needs of the poor. The first Sisters heard the call of God in their hearts, the cry of the poor and they endeavored to live a community life to serve under Louise’s leadership.

Marie de Mandat-Grancey was born into French nobility on 13 September 1837, the fifth of six children, at the Chateau de Grancey in Burgundy. She was privately baptized, with written permission of His Excellency Monsignor Claude Rey, Bishop of Dijon, on 14 September by the Pastor of Grancey-le-Chateau. Marie was the daughter of Count Gaillot Marie Francois Ernest de Mandat-Grancey and Eugene Jean Louise Laure Rachel de Cordoue, spouse of the count.

From the second story window of her parents’ Paris Townhouse at 13 Rue des Saussaries, young Marie curiously watched on the street below as peasant girls, shabbily dressed, walked into the convent that housed the Daughters of Charity. She had been watching this scene since her early childhood when she began spending half a year in Paris and the other half at the de Mandat-Grancey Estate at Burgundy. The family had already been splitting time between the two sites because of the cold winters and low temperatures in Burgundy.

One chapel the Countess chose for family prayer was at 140 Rue du Bac, the residence of the Daughters of Charity. This chapel had become extremely popular a few years before Marie was born. Our Lady had appeared there to one of the novice sisters and asked her to have a medal struck honoring her Immaculate Conception. Later, it was learned that the sister was Catherine Laboure, who would be one of Marie’s teachers.

Marie asked her mother about the peasant girls and the women in the big sunbonnets. Marie first learned then that these special ladies were dedicated to serving the poorest of the poor, and her mother explained how the French Revolution had destroyed religious orders and that the tiny community of nuns actually did consist of peasant girls.

Her mother, the Countess de Grancey, was well-known in the Burgundy area because of her high spirituality that also was a major influence in her daughter’s early life. Thus was born Marie’s faith and her own high level of spirituality.

The countess also visited the poor, the needy and sick people in the region even if their disease was considered contagious. And when the countess was unable to visit, Marie stepped in for her and made the visits. The countess’ example planted a seed that would gradually grow in Marie’s heart.

Marie didn’t quite understand being poor. She had everything she needed, a wonderful home, all she wanted to eat, to wear, the best education because her parents were well to do and lacked for nothing.

Eventually she began to feel the nuns’ great warmth and love for the poor. So touched was her heart that she couldn’t resist the tremendous supernatural charm of genuine charity. She became so touched by their love that a desire to be one of them began to overflow. For whatever reason, she knew she was being drawn to the Daughters of Charity.

After the revolution, the Archbishop of Paris installed the Daughters of Charity on the estage of the Comtes de Lavalliere on the Rue du Bac. It was there that Marie spent part of the year with her family in the Paris townhouse and she was able to closely watch the Dames and Sisters of Charity do their daily work. She appreciated them so much that at the age of 20 – in 1857 – and in the radiance of her youth, in full bloom of her exuberant life and talents, she decided to enter the community of the Daughters of Charity. Marie was in the midst of the greatest promises of the world through her family’s notoriety and wealth, and without having experienced any deception and no other motive than the pure idea of sacrifice and of self-giving, she made the choice. She chose the title “servant of the poor” and sacrificed all the other titles of nobility that could have been hers for the taking.

Marie’s thoughts of serving the Lord were evident in her prayers even at the age of 10. There also was a hint of fear of Him in some of her offerings, but also great love for Him. That was in 1850. But it would be seven years before she would see clearly her destiny as a Daughter of Charity.

Segment 2: How her announcement about becoming a Daughter of Charity surprised the family and their reaction.

Segment 2

The Announcement

Marie’s decision to become a Daughter of Charity shocked her family, especially her brother Antonin. She also writes a letter to her grandfather and explains that she decided to make a sacrifice because of God’s calling and she became totally committed to the daughters.

Marie’s announcement surprised the family and she explained to her Grandfather how God sought her sacrifice in a letter written the night before she left her paternal home for good.

When Marie announced to her family that she desired to enter the company, they were shocked. Word of the Daughters’ charitable works had spread throughout all of France and even beyond. The family greatly appreciated them, but for Marie to become one of them . . . well, that was something that had to be given careful consideration.

Antonin, her brother, strongly objected but he gave no definite reason why. It could have been because Marie would make a complete change in her life, or maybe because of the kind of work which nobility was not accustomed to do. It also could have been her exposure to infection from diseases, but it most likely was because that once she took the step, she would be permanently separated from family.

After the family sat down and discussed it, Antonin withdrew his objection. Marie penned a letter to her grandfather, the Marquis de Cordoue on 26 May 1857:

She wrote in part: The time has come for me to realize a project I have been forming for a long time and what Mom must have talked to you about. Maybe you have already guessed what my decision was.

For too many times my conduct did not match my desire, or what I hope to be my vocation. Often, I am afraid I failed in my duty as a granddaughter, and today more than ever I need to ask for your forgiveness. Please forget, dear Granddad, all you ever had to blame me for. Forgive the pain I might have ever caused you, and do not refuse to give me your blessing in this important step.

Do I need to ask you, dear Granddad, to help me with your prayers in the days to come? Tonight I will have left my paternal home, maybe forever. I do judge myself happy to offer God the sacrifice that He appears to be asking of me in this moment, but I do have a broken heart when I see the regrets I leave behind me, regrets I only well know I deserve. Goodbye, dear Granddad. It is not necessary I hope, to ask you to believe that even in my absence the affection I have for you will always stay the same. A thousand affectionate kisses from your respectful and devoted granddaughter.

Marie.

What made Marie’s decision to join the Daughters of Charity so difficult was that when a young lady entered the DC in that era, she never went back to her own home. The separation was permanent; commitment to the daughters would be total; and go where she is called to go.

The family is noted in French and Ecclesiastical history as both noble and holy. It’s distinguished by the motto, Enmese et Verbo – “By the sword and the word.”

Segment 3: Sister Marie’s first assignment and the duties she undertakes.

Segment 3

Sister Marie enters the seminary, learns much more about serving Christ and receives her first assignment to the House of Mercy in the north of France where she assumes more duties than expected.

Sister Marie’s second step in the daughters Community life was the seminary in 1858, led by a Sister well-trained in the charism of St. Vincent de Paul and St. Louise Marillac and centered upon apostolic life. St. Vincent developed his spiritual life upon service to Jesus Christ in the person of the Poor. She was taught to serve Christ and contemplate Him in every poor person she found suffering, hungry, lonely, thirsty or dying.

To aid in pursuit of this goal, she was given the example of the first country girls who left their families to become Daughters of Charity. How joyfully and gratefully they took to love Christ in service.

People back in 1800 had often talked about published books on the revelations given to a Sister Anne Catherine Emmerich on the Life, Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ and the Life of the Blessed Mother. Sister Marie became familiar with one of the books, expressed interest in mysticism and read and spoke about it. It eventually became a motivating factor in her life at Smyrna.

Sister Marie’s devotion to the Blessed Mother was greatly strengthened through Vincentian spirituality while she attended the Seminary. Seven years prior to the birth of Sister Marie, the Blessed Virgin Mary appeared to a new novice in the chapel where she worshipped. The novice was told to have a medal struck to honor her Immaculate Conception, to open their chapel to the public, and invite people to pray at the altar and seek graces which Our Lady wished to pour out upon all who asked for them. The novice was told to inform the director of the Daughters of Charity to begin a new association and name it “The Children of Mary.” And there was much more, like the need for exactness of obeying rules; devotion to honor the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Sacred Eucharist and St. Joseph. Then there was one additional and appreciative message given to the novice. Mary said to her, “The Community – how I love it.”

In the very year of Sister Marie’s attending the Seminary (1858), the Blessed Virgin Mary appeared in Lourdes. When Bernadette Soubirus asked Our Lady her name, Mary answered, “I am the Immaculate Conception.”

It took great effort and time for Sister Catherine to get any of the requests filled. One of those revelations did impress Sister Marie, one that formed the focal point of her apostolic life: the Children of Mary.

Inside the Seminary, Sister Marie and the other Daughters of Charity lived a quiet, regulated life with rigorous exactness. Outside, however, they could hear some of the noise caused by Communards who created neighborhood uprisings. But the sisters had no first-hand experience with its problems – except when they might accompany a sister to tend to the harmed and injured. Part of Sister Marie’s was to respond immediately to a call from Christ by the numerous people who arrived to seek assistance. Little public record on the information of Sister Marie had been left behind, but it was known that she had to adjust to an entirely new way of life. She was deemed ready within the year for her first mission assignment.

Sister Marie arrived at Aire-sur-la-Lys, a small town on the banks of the Lys and Laquette rivers, in the north of France, on 10 May 1858. She immediately was assigned several responsibilities since only six sisters were attached to the House of Mercy.

Twelve years later, she would be in the midst of the Franco-Prussian War.

Sister Marie’s jobs included the pharmacy, the dispensary, the Office of Benevolence and she handled the tasks of visiting bedfast patients at two small neighboring villages.

In her first mission, Sister Marie seriously strove to fulfill each apostolic work on her schedule. There were fifty-five orphans in the House of Mercy and they, along with sixty young girls from the outside, maintained a nice sewing workshop.

Sister Marie also was responsible for the Children of Mary, their singing class as well as the organization of games for their patronage and their child-care services for the poor. Then during the holidays, she also took on the added tasks of rehearsals for plays and other festive activities.

Because of Sister Marie’s spontaneity, enthusiasm and good will, the youth responded joyously and gratefully. Because of her dedication and handling of the children, some parents were unable to keep them at home, so they lodged complaints and asked authorities to dismiss her. The children actually preferred to stay with Sister Marie, who received full support from her superiors. They responded to the parents with great conviction.

“All right then,” they told them, “do at home for your children what the sisters do and your children will stay with you.”

Segment 4: Sister Marie sets an example for devotion to the children.

Segment 4

Sister Marie admits to her grandfather that it isn’t easy to sacrifice but exhibits how she is devoted to the poor. She takes her first vows and spends 10 years at Aire-sur-la-Lys.

Sister Marie was not only devoted to the young and healthy, but she brought poor children with scalp disease into the house. She combed their hair, mastered the repugnance of her delicate nature that she never tried to spare.

It was easy to work with gifted and joyful children, but Sister Marie, because she was a servant of the poor, began to bring into activities lonely, slow, weak and sickly children. They had a greater need for her help, and her work emphasized even more how much she was devoted to the poor. The most neglected persons were those with scalp disease. She would not let the scabby, bleeding heads with mucous smells bother her.

She began to treat them and became the first to wash their clothes out in the yard; the first to undertake all the heavy cleaning work, all this done by the daughter of a count, who recently had been surrounded by a most brilliant society, gave orders to numerous servants and who had access to all the pleasures of life.

Sister Marie did all these things without any noticeable effort, just like it came as a routine task. She described her actions in one paragraph of a letter to her grandfather:

“It is true that my not-so-very generous nature wanted to refuse the sacrifices that I was called to do, and I can assure you that as a result, one has to suffer cruelly, but God does not refuse His grace to those who, at the bottom of their heart, wish only what He wishes and I have now myself experienced. How well He knows how to alleviate the burdens that seem to be the most crushing.”

A zealous evangelist, Sister Marie could boldly confront people from all walks of life and tirelessly strive to convince them of the need for conversion.

A Newsletter described her thusly: “Her good nature, her simple and straight-forward ways, her energetic and somewhat brusque manner of speaking plus her sharp wit helped people receive from her what they would not have received so well from anyone else.”

Daughters of Charity do not take vows until they have lived five to seven years in Community. The sister Servant – the local superior – or another is assigned to assist her during the course of the next year as she prepares to take her first vows. These vows begin with a review of her first vows that every Catholic makes – her Baptismal promises. She will then proceed to determine what it means to vow poverty, chastity, obedience and service to the Poor.

For the Daughters of Charities, it was different. Once the Archbishop of Paris approved their working as a religious community in Paris, they were able to work freely in the archdiocese. He had a right to evaluate their work, but did not have a right to alter their internal community life.

How and what they agree to live with is what was approved by the Church in their Constitutions. For the Daughters, it was the core of what Sister Marie studied for her vows and what she had already lived since she joined the Community in Paris.

In poverty, she is allowed to retain ownership of the personal funds she had at the time of her entrance into the Community as well as any inheritance she receives. She may accept personal gifts and further exercises the vow when it comes to spending any of these funds. With permission, she may use these funds for the poor and for good works and projects in accordance with the teachings of the Church.

The Daughter of Charity herself may be a poor person, such as Sister Catherine Laboure, who had little to no education, no funds to give, only an open, loving heart. Or she might be a wealthy person who can aid hundreds of people from her own personal funds . . . that is, if she gives without expecting anything in return but the love of Jesus Christ.

Before taking vows, Sisters in a local mission give to the Sister Servant their opinion on the readiness of the Sister who wishes to take vows. The Provincial Superior and her Council make their recommendations to the Superior General of the Congregation of the Mission on whether he should grant Sister’s request for vows. The vows she takes are for one year duration, renewable with permission each Feast of the Annunciation.

These reserved vows can only be dispensed by the Superior General of the Congregation of the Mission or by the Pope and not by any other. At the end of the year, she is free to depart from the Community. However, to take the first vows, it is done with the thought and intention that this is what the Sister wants for the rest of her life.

After she secured permission, in the presence of her local Community in Aire-sur-la-Lys, Sister Marie pronounced her vows in the company of the Daughters of Charity on the Feast of the Death of St. Vincent de Paul – 27 September 1862.

That morning, like any other morning, Sister Marie went to work. She remained in the mission for eight years. Then, on the Feast of the Annunciation, she, like all other Daughters of Charity, silently renewed her vows.

At the time of the cholera epidemic of 1865, a procession was planned in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary to counter the disaster and attempt to preserve the city. Sister Marie, in the charge of the choir which also gave her a little authority of a vicar, went to see the dean to ask that the procession pass by a specific street.

“But that’s impossible,” said the dean. “It’s a long route and you know that it takes twelve men to carry Our Lady Panetiere (heavy stone statue of the old Madonna venerated in this country).”

“It’s of no importance, Mr. Dean,” Sister Marie answered. “There is in this street a protestant to be converted. Take this street; the Blessed Virgin will convert her!”

Sister Marie won her case. The procession, indeed, took place under the eyes of the protestant woman, who was edified. The woman, in good health in the morning, came down with cholera in the evening, and faced with death, begged for the help of the Catholic religion.

Segment 5: After ten years at Aire-sur-la-Lys, Sister Marie is sent on to Le Pecq.

Segment 5:

Second Assignment is to the small orphanage at Le Pecq, a Paris suburb, during the Franco-Prussian war that caused a great number of orphaned children. It’s here that Sister Marie displays her great ability to organize.

Sister Marie’s new job at Le Pecq was to head an orphanage that had expanded far beyond its capacity due to the Franco-Prussian war. That conflict began in 1870 when France and Prussia were at odds over the regions of Alsace and Lorraine. It caused severe conditions and resources were scant, but she would not be denied on behalf of the poor orphans.

The Germans won the short war and claimed that the two regions were rightfully theirs, but the majority of people living there were French.

Le Pecq is located in a loop of the Seine River about 11 miles west of Paris and at the foot of the castle of Saint-Germaine-en-Laye. Its territory is distributed on two banks of the Seine and includes the small Corbiere Island.

Sister Marie displayed organizational leadership qualities developed during her time at Aire-sur-la-Lys, which became so familiar to those who knew her. She had already been recognized as a community visionary and named Sister Servant.

The war brought a disaster to Le Pecq where great numbers of children were orphaned. When Sister Marie arrived there, the number of orphans had just doubled, so she mustered her forces, then learned that another group of orphans had just been dropped off for the care of the Sisters. That tripled the number of children at the orphanage.

The Sisters sought the help of Le Pecq’s citizens. It was here that Sister Marie displayed her great leadership qualities and explained how they should seek the assistance of the people.

She had the courage to beg in the streets for food, clothing and beds, “for your children, the children of Le Pecq.” And she challenged local citizens to support and recognize the efforts of the poor sisters, and the people responded.

The people soon discovered that Sister Marie had a sense of righteousness and responsibility and that she was very direct in expressing it. Some said she was blunt, but none thought of her as offensive. Citizens also learned that she trained her sisters to say, “Please help us to care for your children.” She wanted people to know that the responsibility to care for these orphans truly belonged to the people of Le Pecq and not to the Sisters.

About four years after Sister Marie’s arrival, she was asked to receive a young Sister Jeanne, who had just completed seminary. She was told there was a question of whether the new Sister had a vocation, that she had the desire to be a Daughter of Charity, but that she seemed physically unfit for it.

Sister Jeanne still had four years before she must take the vows, or be dismissed. Sister Marie accepted the challenge, set up a schedule for Sister Jeanne – massage, exercise and work periods – and also became her therapist, counselor and spiritual aide, and soon she began to show improvement.

During the twenty years of Sister Marie’s leadership in Le Pecq, local authorities and Daughters of Charity in Paris decided that there no longer was a need for an orphanage. The Sisters mission had been accomplished.

Segment 6: A whole new world was about to open up for Sister Marie.

Segment 6

When Pope Leo XII put out the call for missionaries to serve in the Middle East in 1886, Sister Marie was nearly 50. With the Le Pecq orphanage to become history, she answered the call for what would be her last assignment: The Navy Hospital at Smyrna, Turkey. It would be her most exciting assignment of all.

As the ship entered the harbor at Smyrna, Turkey, which lay on the coast of the Aegean Sea, Sister Marie de Mandat-Grancey gazed out at the big city and wondered what lay ahead of her. Smyrna, mentioned in the bible, is the third largest city in this Muslim country.

When Pope Leo XII put out his call in 1886 for French missionaries to serve in the Middle East, the Daughters of Charity felt the orphanage at Le Pecq had served its purpose. So Sister Marie, approaching 50 years of age, answered the Pope’s call. She sailed for Smyrna where she was assigned to the order’s hospital and upon her arrival, discovered the facility was under supervision of the French Navy. Her job would be to nurse both civilian and military personnel. In answering God’s call to serve the sick and suffering, she was totally committed to His Divine guidance.

In the early 14th century, King Francis I signed a trade treaty with the Muslim Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and France began to develop as a world power. That treaty shocked other world powers. In the ensuing centuries, France developed a Navy of galley ships for trade and warfare over the entire Mediterranean Sea.

Aboard one of those ships was Vincent de Paul, a young priest and passenger en route back to France after he had collected a bad debt for a woman who had bequeathed money to him. The ship was captured by pirates and Vincent was taken off and sold as a slave to a wealthy Muslim man in northern Africa. When his owner died, he became the property of another man, but when Vincent managed to convert his new young owner to Christianity, he was set free in 1607.

When Pope Leo XIII asked for volunteers as missionaries and assistants, it was natural for him to seek aid from France. Vincentian priests and brothers along with other French clergy were already stationed there. Thus Sister Marie, with a family background of members who joined in military forays and with her nurse’s training, was quick to volunteer.

Ah! Smyrna! Sister Marie was familiar with Smyrna because of John the Evangelist’s writings in Chapter 2 of the book of Revelation.

John was a prisoner at that time on the island of Patmos, located about fifty miles south of Ephesus, because he had proclaimed God’s word and gave testimony to Jesus. Patmos was located in the Aegean Sea and one of the Sporades islands used as a penal colony by the Romans.

As Sister Marie left the ship after it docked at Smyrna, she was well-aware that she was not arriving alone. Sister Rosalie, who had been in charge of the sewing room at Le Pecq, was with her. And there waiting to give her a great welcome was the robust, grateful Sister Jeanne, whom Marie had nursed back to health several years before also at Le Pecq.

The hospital facility had been active since the Crimean War, but afterward, the French had neglected it, lost interest, the military failed to support it and it had become severely dilapidated physically and lacked equipment. On her first walk-through, she was certain that her new mission needed much care. In fact, it was in dire need of total repair by dedicated workers. It could not continue to properly function as a hospital without new equipment. That was its greatest need. The Naval Station had closed when the war ended, but the hospital remained in operation even though ships had no reason to anchor at Smyrna.

Not only was it in dire need of new medical equipment, but living quarters of the medical staff needed improvement. This impoverished facility would be her home for the rest of her life.

Sister Marie at age 50, is filled with enthusiasm for this new mission. There was plenty of work to be done and she already knew the strengths of the two sisters with whom she previously had worked and lived.

Sister Marie also knew she was in a Muslim land and would need to cultivate a proper relationship to this non-Christian population. She didn’t know how it would work out, but she knew she had to make it better for all of them. She would depend on her beloved patroness, the Blessed Virgin Mary, for guidance.

Segment 7: The task of making a change in the atmosphere of an entire area is launched by Sister Marie.

Segment 7

Sister Marie undertakes the task of repairing the Naval Hospital and living quarters, much at her own expense. She also seized the chance to attempt to change the moral attitude of the city and launch another unit of Children of Mary.

Despite the state of the hospital, Sister Marie didn’t throw up her hands in despair. She focused on what was missing and continued to express her total gift of self to God with complete faith and trust in His generosity and love. It was typical of her behavior.

Within a short time, workers were making repairs in the hospital wards, new equipment began to arrive to replace the old dilapidated pieces. Painters quickly began to brighten rooms and corridors. That gave a whole new look to the wards of the patients.

Next came the quarters of the medical staff. That area received a complete makeover and provided more comfort and attraction. The old Sacred Heart Hospital took on a new and somewhat vibrant look.

Very few people knew that most of the costs were furnished from Sister Marie’s personal funds. But the living quarters of the Daughters of Charity remained untouched. Their area was considered the poorest religious residence in all of Smyrna.

Sister Marie and the other Daughters of Charity made the hospital more comfortable for the Navy patients and also for the doctors and nurses who took care of them. With her strong direction and will, they restored the facility, her own financial resources used whenever necessary.

When naval ships stopped at Smyrna several sailors would make quick visits to the sisters. It seemed most of the sailors knew Sister Marie had a royal brother in the Navy so many went to visit her. They were the ones who received grand treatment with a fine meal.

The restoration included the addition of rooms for young girls to keep them off the streets and to establish a small classroom for sick children. This addition blossomed into workshops and a full-fledged school.

When the Naval Station became operative, a new subdivision for the working class was opened next to the naval base and the hospital. Since a great number of children were housed in the new area, the town was in dire need of a school so the sisters were asked to operate it. Like in many other institutions of the Daughters, it was another task added to their responsibilities.

Sister Marie saw this as a great opportunity to change the moral climate of this port city that was already known for some rather sordid activities by its floating population. Not only did the children need religious instruction, but she wanted to begin immediately another unit of the Children of Mary as a help to reform this area which had once been known for its apostolic settlement.

By the time Sister Marie was appointed Sister Servant of the Daughters of Charity in Smyrna in 1890, she had established the Children of Mary in order to catechize the children in her charge. She would be the Sister Servant for the next 25 years, until her death in 1915. Her effort was costly and depleted her fortune so that later, when an opportunity arose to acquire the property containing the Blessed Virgin Mary’s house, she needed financial assistance from her father. It would be the only time she’d return home to Burgundy after she became a Daughter of Charity.

As Sister Servant, she assumed other duties such as Sister in Charge, school principal, teacher of nursing, Director of the Children of Mary and she was sought to be respondent in every need. She had been so enthused in this apostolate, it was similar to her early days on mission. It was a thrill to be in a beautiful classroom, to once again train girls in a new sewing shop and share her talents in needlecraft.

Then in 1895, she used her personal funds to build a hospital pavilion. Youthful girls who came to Smyrna to seek work could find inexpensive housing, and some of the unemployed were given temporary shelter.

Over the years in her various missions, she taught many youth the arts of penmanship, printing, coloring, all the handicrafts used to beautify wall hangings, banners, and stationery, etc. Sister Marie had substantial revenue to spend each year. It all went to charities, for the needs of the hospital or other works of the house, and to poor children in classes, the dispensary and visits to the poor in the neighborhood. Sometimes she provided revenue for the diverse needs that solicited her good will from all sides. The question was, how much did she give to all kinds of people and on every occasion? How many discrete and well-placed charities? How many times was she taken advantage of in an undignified manner?

Over time Sister Marie sold off several properties and liquidated stocks and other assets. She finally eliminated her regular sources of income. As a result, she wasn’t able to alleviate the growth of suffering around her as much as she wanted and it caused her intense misery.

Segment 8: Sister Marie uses all of her talents and also finds Father Eugene Poulin.

Segment 8

Sister Marie was blessed with many talents and as a teacher she put them all to use on the youth of Smyrna. It was here that she met Father Eugene Poulin, ordained a priest in 1867 and arrived in Smyrna about a year after Sister Marie as a superior, ready to lead the high school and the Mission.

Through her education, Sister Marie became a wonderful artist and shared that in every possible way. Her talents were so many. She could train the choirs and to the extent circumstances would allow, her repertoire comprised of only serious choral compositions on a sacred text without instrumental accompaniment. She used beautiful music, religious canticles worthy of the name.

As a painter, she decorated banners, outer vestments for the celebrant at the Eucharist and vases for the altar. Her needlework was precise; she embroidered with great patience and, with a composite all her own, vestments, copes, canopies and altar frontals. Perhaps her greatest love was to weave traditional, pious emblems as well as beautiful texts from the Holy Scripture.

As a dedicated teacher and mentor of young girls, Sister Marie’s maternal zeal for the youth of Smyrna brought out her emotional side at the close of classes each year. She worried terribly about what might become of the children in that seaside town that possessed every imaginable scandal and vice.

She would say to them, “Don’t forget the lessons of the catechism. Keep holy Sundays and don’t neglect the sacraments because all these things are more necessary to you than ever and the service of God should not be interrupted. The chapel will remain open, take advantage of it. Also, the hearts of the sisters are always open to you and I cannot emphasize enough their regrets at this moment. Come and see them.”

One Sunday evening shortly after Sister Marie became Superior in Smyrna, she asked a visiting Vincentian Father, Eugene Poulin, to choose a spiritual reading for the community during dinner, a custom of the Daughters at that time. Father Poulin unintentionally took down a book that seemed to jut out a little from the others. It was the volume “Life of the Holy Virgin,” which the sisters had been regularly using to read from, and it contained the visions of Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich, the 38-year-old Augustinian nun who was confined to her bed during the time of the Napoleonic wars.

Anne Catherine had been given a gift of visions of the life and death of Jesus and His Mother, the Blessed Virgin Mary. Father Poulin chose to read the passage of the revelation that described the Holy House of Mary at Ephesus.

Father Poulin, C.M., director of the French Sacred Heart College at Smyrna, Superior of the Vincentian Fathers and professor of Classical Languages, sat at the table. He was a rigorous classical scholar and scientist, and disgusted with the priest’s choice since he was opposed to all forms of mysticism.

Father Poulin was born on 4 July 1843 in Montillot, near Vezelay (Yonne). As a young man at the rectory in Chamvres, home of his uncle the Abbot Fournier, Eugene showed the most agreeable disposition toward his studies. The good pastor declared that his nephew would go far and Eugene went farther than even his uncle thought when he was called overseas to become one of the glories of the Lazarists.

Eugene was ordained a priest at Saint-Lazare on 15 June 1867 and kept such

good memories of the seminary at Sens that he sometimes made unfavorable

comparisons with the Mother House. Named to Montpellier where he passed some time in 1887, he left for Smyrna in the capacity of superior.

He was ready to lead at Smyrna, the high school and the Mission which had

just merged into one house. Father Poulin argued that given the debilitating heat of the climate at Smyrna, “I will not last six months!”

He lasted 39 years.

Segment 9: Father Poulin reads for Sister Marie even though he didn’t believe in mystics.

Segment 9

Father Poulin encounters Anne Catherine Emmerich’s book despite his disbelief in mystics when he reads for the Daughters of Charity on a Sunday night. And then the extraordinary happens to him and he finally relents.

The DC sisters had already heard of Mary’s sojourn and death in Ephesus, so when Father Poulin had finished reading from Anne Catherine’s book, Sister Marie began to speak glowingly about the revelations.

“Ephesus is not very far from here,” she said. “It might well be worth the effort to go there and see!” And she wondered what would be there now.

Sister Marie was inspired by what the Vincentian had read, but Father Poulin let it be known that he didn’t care about this mysticism business that Anne Catherine had written about in her book. He was a student in science and the classics, but when the priest had finished the reading, he took the book and opened it to the marker. He began reading about Mary’s home in Ephesus and his thoughts centered on the fact that he wanted to prove Anne Catherine Emmerich wrong.

Father Poulin wrote in his journal, “The Holy Virgin’s House,” about how he already encountered Anne Catherine Emmerich when one day in Mid-November 1890, Sister Maire, Superior of the Providence, asked him for a book to read in the refectory.

“Of course, Sister,” Father Poulin said and he went to the library, collected several books and took them to his room to determine which one would be appropriate for her. One of the books was an old in-octavo bound in sheepskin, in bad condition, that he had taken without realizing it. Reading the title page, he felt a surge of eagerness.

His mind wandered back to when he was about 25 years old, at Gregy, near Melun, which was under the leadership of the Venerable Father Denys, former Superior of the Great Seminary at Carcassonne (Evreux). Father Denys also held the title of Visiteur of Province de France and Superior of Gregy. The good father was very pious, very devoted to mystic studies. Father Poulin recalled how, with a childish faith, Father Denys spoke to the group during evening recreation about his favorite reading matter: Catherine Emmerich, Marie d’Agreda etc etc.

Father Poulin and his associates had no esteem for any of these women visionaries and they laughed so much at the joyful jokes they made each time the holy man brought up the subject he cherished so much.

It wasn’t a momentary impression. It was a foregone conclusion and for twenty years, Father Poulin never believed a single one of the visionaries. He believed he would be demeaned if he read only one page of Marie d’Agreda or Catherine Emmerich or Sainte Gertrude or, indeed, any of them.

That’s how it was until Father Poulin, in November 1890, glanced over the old in-octavo and read “The Suffering Passion of Jesus Christ, according to Catherine Emmerich’s Visions.”

He quickly removed the book from the stack he had brought to his room, disdainfully put it aside on the table and kept on looking at the other books. He found one for the Sister, gathered up the rest and returned them to the library. The next day to Father Poulin’s surprise, the book he had so disdainfully tossed aside was still on his table in the same place.

“Strange,” he thought. “How could I have forgotten it yesterday? The book is thick and quite visible . . . but that’s enough. I have some other books for the library and I’ll take it back with them.”

The next day, however, The Suffering Passion of Catherine Emmerich was still on his table. It seemed, he thought, that he had taken it back to the library. “Of course . . . I had intended to, but I had not done it.”

It was the same the next day . . .and for the next two or three days.

“Is this book making fun of me?” he asked himself out loud. He finally threw the book violently into a corner of the room. It fell with its pages open and broken in two.

“Well done!” Father Poulin said with self-satisfaction. “Stay there and don’t annoy me anymore.”

A week passed. The book was still on the floor, same place, same position. He laughed every time he looked at it, felt a little childish revenge each time he saw it.

Father Poulin thought, one should be aware that many times we are guided more often than we guide, that this might be a sign of providence, a sign that tells a lot. It suggests we have the trust to finish a task and also gives us the necessary courage to go forward.

“Could it be understood,” he wondered “ why I spent one week in front of the book that was so hateful, that seemed of so little value without any thought of picking it up to see what it was about?

“Strangely, the man who cleans my room didn’t pick it up or put it elsewhere . . . oh! no . . . I don’t say miraculous, it is strange, extraordinary.”

About six o’clock one morning when Father Poulin returned to his room after morning prayers, he took a look at the unfortunate book. Blood pounded in his veins, a reflection came into his mind. “Really, it’s neither wise nor right to be against a book without knowing it, to condemn it without having read it, either.

“This reflection changed something in me,” he thought. “Was it not ridiculous that for twenty years I had ridiculed the book and the writings of Catherine Emmerich without having read a line, without knowing who she was?”

To get the book, he had to take one step, but when he picked it up and tried to open it, a deadly aversion came over him. “Do open and read it,” common sense was telling him, but repugnance stopped him.

He stood for about five minutes, the book in his hands, unable to decide. “Had it been only ‘Passion?’ I could have read it easily, but for that epithet ‘suffering.’”

The “suffering passion of Jesus Christ” was full of mysticism and this horrified him. After thinking hard about it, he thought “I’ll read a little, just to see who this Catherine Emmerich is that doesn’t engage me. I am not obliged to read the whole book.”

Segment 10: Father Poulin begins to read and makes a startling discovery.

Segment 10

Father Poulin didn’t intend to read all of the Catherine Emmerich book, until he started and made the startling discovery of how well and simple it was written. Then he finally convinced his colleagues and they were all interested in Ephesus and Mary’s house.

Father Poulin, satisfied with his good decision about reading the book, opened it, then became ashamed. “I didn’t wish to be seen with this book in my hands!” So he stood by the corner of the table ready to throw it down if somebody should knock on his door.

“I read the foreword first . . . Let us go on! . . . then the preface, then the third . . . a note concerning Catherine Emmerich. Here we are! I started to read this note slowly, looking for some stupidities or extravagances.

“You can imagine my surprise! It was something very pious, very simple, all conforming to good sense; I was astonished! There was sweetness, words and style which invaded you slowly, going straight to your heart.”

He read on, charmed by the text when the big bell rang. “What! Seven o’clock already!” He had been reading for an hour and was thrilled. He left the book open, placed it on the table and left for the church. At eight o’clock, he was back, took up the book again and began reading. This time, he didn’t hide. He read the note on Catherine Emmerich until the end with delight in everything he was reading and everything he was learning . . . but he still wasn’t a convert.

Following the note there was a title in big black letters: The Suffering Passion of Jesus Christ according to Catherine Emmerich. When he looked at the title, all his repugnancy returned. But this time, Father Poulin overcame it. He turned the page; continued reading. “I had never read anything so pious, so beautiful, so interesting about our Lord’s Passion . . . except the gospel. I wasn’t reading,” he said. “I was devouring the pages.”

Father Poulin was anxious to share his unexpected illumination. Only his colleagues didn’t agree with him and they let out a loud sigh of disagreement.

“But do read it,” Father Poulin answered. “Read and you will see.”

“Me . . . reading things like that,” one replied. “I have no time to waste!”

“If I read it,” a fourth associate said “I must go to confession.”

And the jokes continued. Everyone laughed. Father Poulin was alone against the opposition and despite his arguments, his exhortations, he failed to convince them.

From that time on, each evening or during recreation, or occasionally because of his reading or because of some reflection, there were amicable arguments.

Finally, one evening in early January 1891, the group eagerly argued about Catherine Emmerich. One of the elders, Father Dubulle said, “Mother Superior; I was like you, unbelieving, and without any will to read. But then I read it and now I believe what it says.”

“Oh! I don’t believe it at all,” Father Poulin quickly responded. “But I agree, it is very simple, very pious, very right and very interesting.”

“Have you read the Holy Virgin’s Life?” Father Dubulle asked Father Poulin.

“No . . . I don’t know if it exists.”

“Would you like to read it?”

Father Poulin looked at Father Dubulle for a few moments. “Of course . . . with pleasure.”

Father Dubulle left the room and a few minutes later, returned holding a small book bound in black entitled: “The Holy Mary’s life according to the visions of Catherine Emmerich translated from German by the Abbe Calzales,” etc.

Father Poulin took the book and started to read it like he did the suffering passion of Jesus, with a delicious feeling. There was that same piety, simplicity, the same rectitude, the same attractive unction and the same interesting facts and sayings.

As he read the last chapters where Catherine Emmerich wrote about Mary’s stay at Ephesus, her house, her death and her grave, he exclaimed, “What’s this? I had never thought in my life of Jerusalem or Ephesus, or of Ephesus more than Jerusalem! I had never had the opportunity of any revelation!”

Meanwhile, the question was transformed and full of interest for all of them. They were in Smyrna and thus interested in Ephesus.

During the first recreation, Father Poulin loudly announced his discovery to everyone. “Hey . . . all of you, listen, listen to me! I’ve found the answer!”

Thus, the discussions started again but with more passion than before. For the next weeks and months, it was the primary topic of their conversations.

Then, by common agreement, they adopted a resolution: “It’s quite easy,” one said. “We can go and see if it’s true or it isn’t. If it’s true, we have to accept the evidence; if it’s not true then we finish with Catherine Emmerich; she will be considered to be only a visionary, thus nobody will speak about her anymore.”

Segment 11: After several discussions, Father Poulin and his colleagues come to a decision: go to Ephesus.

Sr. Marie De Mandat-Grancey Foundation

P.O.Box 275

Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724 USA

P.O.Box 275

Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724 USA

" I am not a priest and cannot bless them, but all that the heart of a mother can ask of God for her children, I ask of Him and will never cease to ask Him." ~ Sister Marie

“The grace of our Lord be with us forever.” ~ Sr. Marie